Apologies for the extremely sparse posting of late. I have just returned from a trip to Central America, including Belize, Honduras, and Mexico, which I’ll post more about soon. In the meantime, I’d like to share the first edition of a weekly column I began writing for the Independent (Rwanda edition) three weeks ago. I’ll be posting these weekly after they are published online. I look forward to your comments and feedback.

Beyond the state: letters from Gulu

Published online November 23, 2011

Health care, education, basic infrastructure, and security are some of the services the modern state seeks to provide. The success of states in delivering these goods to their far-flung populations, especially in the midst of conflict or under severe resource constraints, is quite variable. In recent years, for example, Rwanda has been lauded for implementing a health insurance scheme that covers all Rwandans and offers them a range of health services, while the reach of the state in countries like the Democratic Republic of Congo or South Sudan is much more limited. While there are important lessons to be learned from the success of the Rwandan state, which has proven itself unusually efficacious in a number of sectors, it is all too easy to overlook the ways in which information and innovation flow alongside the state, and often in spite of state failures. Tremendous opportunity lies beyond the state.

I recently unearthed letters given to me in mid-2005 by a group of primary school students in Gulu, northern Uganda’s largest city, illustrating this point. At the time, to cross Karuma Falls, where the Nile cuts the land like a scythe, was to enter a world far removed from political drama unfolding in Kampala. While Ugandan President Museveni was jostling for the removal of term limits in the capital, the terror of the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) in northern Uganda was still unfolding, though nearing its final days. The river dividing north from south might as well have been an ocean.

The reach and strength of the state was limited. Getting to Gulu from the capital carried its risks – tarmac fell away at the edges of the road much of the way from Kampala to Karuma, rebels lingered somewhere north of the Nile, and reaching the environs beyond Gulu was an even greater challenge. The state could not guarantee security, much less provide quality public services. Then Prime Minister, Apolo Nsibambi, in charge of public sector management, did not even set foot in the north until the mid 2000s, more than five years into his term.

When I first received the letters, I was struck by the violent images many of the children in Gulu could portray with a couple of pens and a piece of paper. Looking back, however, more striking than these images are what these youngsters wrote. “Too many children one after the other”, wrote a young boy named Geoffrey. “If a woman is not allowed to rest between children, her reproductive system can be harmfully affected, and her children will not be properly cared for”. Another, Solomon, carefully printed Ghanaian Nobel laureate Raphael Armattoe’s poem, “The Lonely Soul”, word for word. Others wrote about the effect of AIDS on their community, and a young boy named Kenneth drew a picture of “Cent 50”, the American rapper.

These letters illustrate not the failure of the Ugandan state in the north, which had evidently been unwilling or unable to stop the marauding LRA for nearly twenty years, but rather the porous nature of society, and the tremendous opportunities that lie outside the state. These students demonstrate not the dismal quality of Uganda’s educational system in an insecure region, but rather their ability to utilize the resources at their young fingertips. At ages seven to ten, they shared information about child spacing, antenatal care, infertility, the spread of infectious disease, poetry, and American pop culture. Through what channels did they initially access this information? Through school and formal state structures? Possibly, though these are likely to be only part of the story. How can we use these channels, whatever they may be, to further promote innovation and the spread of information?

Our approaches to improving public health and education have often focused on things we can touch and see – a health center, a new classroom, an operating table, a chalkboard – but ignored the social networks and flow of information that do not respect administrative boundaries and are not tied to specific politicians and policies. This bias is in part due to the fact that physical infrastructure is highly visible, and as such, plays an important role in politics. It is much harder to see the networks of common knowledge than it is to see the building of walls. It is easy to undervalue and difficult to use that which we cannot see, at least politically. We tend to privilege infrastructure over information.

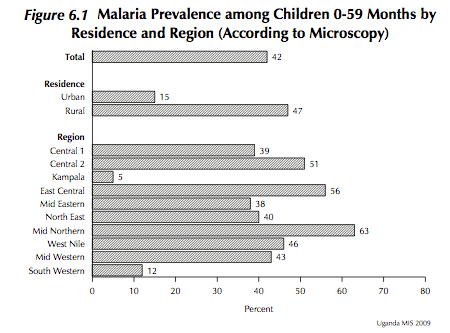

How do we take advantage of the vibrant flow of information today? How can we better understand the channels through which it flows – through communities, families, churches, mosques, media, and even music? The state is not the only, or even primary, conduit of knowledge with the potential to improve health, for example. The formal structures of the state and public service provision often seem to fail us – absenteeism among civil servants, rampant corruption, poor policy implementation – but the social structures that connect society have the potential to fill in the gaps.

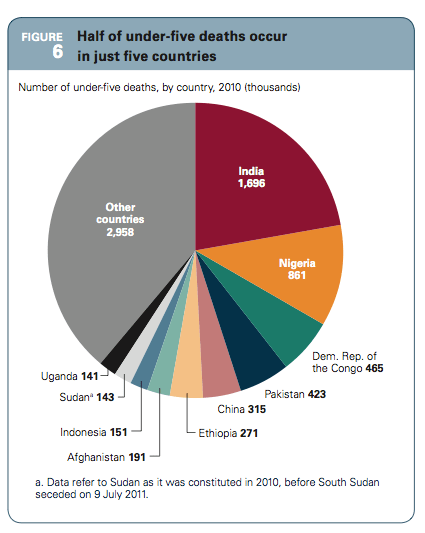

What is remarkable is not how far we have to go in ensuring a minimum standard of living, which can seem like a daunting journey, but how far we have come, even in the midst of conflict and severe resource constraints. The state can and should play an important and perhaps guiding role in providing public services, but we should also try to understand and take advantage of the opportunities to improve health, education, and other social services already at our fingertips.