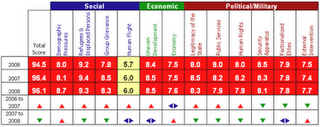

Uganda was last week ranked among the top 20 countries most vulnerable to state failure, according to the 2008 Failed States Index, produced by the Fund for Peace and Foreign Policy magazine. With a score of 96.1 out of a possible worst of 120, Uganda ties with Ethiopia for 16th most vulnerable, and fairs just marginally better than North Korea (97.7), Haiti (99.3) and Burma (100.3). Shocking? Not to Leader of the Opposition, Professor Ogenga Latigo. “I am not surprised,” he says, given the current political situation where rule of law is often non-existent and where the government is king. “Even police say they are acting from above, not according to the law,” says Latigo. The index comes to similar conclusions, ranking the military, judiciary, police and civil service as “weak,” and the quality of leadership as “moderate.”

Countries were scored based upon twelve social, economic, political and military indicators, and data was collected between May and December 2007 from over 30,000 open-source articles and reports. Uganda has barely improved since the 2007 Index, where it was ranked 15th most vulnerable. Does the Failed States Index do the country justice? Is Uganda in critical danger of becoming a failed state?

Of the twelve indicators, Uganda ranked the worst by far in the category of Refugees and Displaced Persons. Uganda is the third worst performing country worldwide in this category, only above Somalia and Sudan. According to the Uganda country profile compiled by the Fund for Peace, Uganda’s score is attributed to high numbers of refugees and people residing in internally displaced person’s (IDP) camps. The report states that Uganda hosts nearly 270,000 refugees from Sudan, Democratic Republic of Congo and Rwanda, and that there are nearly one million IDPs in Northern Uganda.

Uganda has been host to refugees from around the region for years as its neighbors have fallen into full fledged state collapse. This, however, would seem to indicate that the country is a safe haven for the region, not that Uganda is on the verge of state failure. Nevertheless, Nate Haken, an associate at Fund for Peace, explains: “If a country hosts a large number of displaced people, it puts pressure on the state because of the logistical challenges involved in feeding, housing education and protecting them. Additionally it puts a drag on the economy because when people are displaced, the community structures break down and people are unable to meaningfully participate in the workforce. All of this increases the potential for instability…”

State Minister for Relief and Disaster Preparedness and Refugees, Francis Musa Ecweru, does not believe this to be true in the case of Uganda, “The influx of refugees has done nothing to compromise our stability as a country,” he says. Although he adds, “It only puts pressure on law and order enforcement, because not all refugees are law abiding people.”

Roberta Russo, country representative for UNHCR, agrees with Ecweru. “I wouldn’t say it increases vulnerability,” she says, “but rather the opposite,” especially in light of the fact that sometimes Ugandans themselves benefit from the provision of services provided to refugees. She also says the situation with regard to refugees is improving. “First of all,” she says, “from Sudan we are repatriating a lot of refugees – over 60,000 since the beginning of the year, and many have returned spontaneously. In DRC the situation also seems to be improving since peace talks in Goma began.”

Moses Okello, head of research and advocacy at the Refugee Law Project, agrees that the ability of refugees to destabilize a country is an “overexageration,” particularly in Uganda. Rather, “What has been problematic,” he says, “is the government of Uganda using refugees for their own political purposes.”

The Fund’s Uganda country report rightly points out the fact that hundred of thousands of Ugandans are themselves displaced as a result of the over 20 year war between the government of Uganda and the Lords Resistance Army. But the miniscule improvement in Uganda’s score for this indicator since last year perhaps does not give enough credit to the very real progress that has been made in Northern Uganda. “The number of IDPs is decreasing extremely,” Russo says, “We now have less than 700,000 in camps.”

This is still an unacceptably large number of displaced people, but does it mean that Uganda deserves to be ranked third worst in the world? Okello says, “To a large extent I think that’s really fair…the government of Uganda for a long time managed to keep it [the conflict in Northern Uganda] under wraps…For a long time the international community did not know the scale of the conflict.” He argues that the government of Uganda was so concerned with perfecting their own image that they refused to call the conflict an emergency situation, which would have allowed international intervention at an earlier stage.

Despite the past mismanagement of the conflict, however, the government of Uganda is now well aware that there is much work to be done. Ecweru readily acknowledges the lack and inadequacy of public services in Northern Uganda, such as health facilities and basic infrastructure. Recovery of the north is next on his agenda. “We have to prepare them to recover…before they can graduate to development.” Perhaps with the recovery and resettlement of IDPs over the course of the next year, Uganda’s score will improve next year.

According to the 2008 index, Uganda has improved, albeit marginally, on a number of indicators since 2007 such as Group Grievance, Legitimacy of the State, Public Services, Human Rights and Security Apparatus. The indicators for which it has worsened are Demographic Pressures, Economy and External Intervention.

While demographic pressures are apparent in Uganda, with a population growth rate of around 3.6% — one of the highest in the world – it is less clear that the economy and external intervention have worsened in the past year. During his June 2008 Budget Speech, Minister of Finance, Dr. Ezra Suruma announced that real GDP growth in the fiscal year 2007/08 was estimated at a whopping 8.9%, much higher than the already commendable 6.5% that had been projected in the previous year’s speech. Though the Fund for Peace arguably did not have time to include this re-estimate in their calculation it was still clear during the research period that the Ugandan economy had been experiencing tremendous growth.

Nevertheless, the country report justifies its reasoning in assigning Uganda a worse score for its economy this year by stating: “…despite the country’s wealth in natural resources and a high GDP growth rate of 6.5%, political instability and mismanagement have left the economy undeveloped and poor.” To be certain, Uganda remains a developing country with a still nascent economy, but with a real GDP growth rate of 8.9%, it seems wildly unfair to even hint that the country is in “sharp and/or severe economic decline.”

In terms of the External Influence indicator, the Fund for Peace explains Uganda’s worsening score by stating, “The World Bank has 20 active projects in Uganda, with $1452 million committed in all sectors. In addition to foreign aid, Uganda has received considerable international attention due to the conflict with the LRA.” There is no doubt that Uganda receives a massive amount of foreign aid, but as a percentage of Uganda’s total budget, this figure has been decreasing. Whereas only a few years ago around half of Uganda’s budget was donor funded, according to this year’s budget speech, that figure is now closer to 30%. While Uganda still has a ways to go in making itself completely independent of donors, it may be unfair to say that the situation has gotten worse in the past year. Additionally, it is hard to see why Uganda should be penalized for the increased international attention the conflict in Northern Uganda has received and which very may well have assisted in finally bringing peace to Northern Uganda.

Ranked in the top 20 most vulnerable states, Uganda is in the “critical” zone for state failure. The Fund for Peace emphasizes, “It is important to note that these ratings do not necessarily predict when states may experience violence or collapse. Rather, they measure a vulnerability to collapse or conflict.” The Failed State Index is useful in that it looks at a broad range of factors that have the potential to induce or reduce the chance of conflict or societal deterioration. If the index can be used to accurately predict conflict, perhaps countries and regions can use it to prevent or mitigate violence, which, for example, could have saved hundreds of lives in Kenya, South Africa and Zimbabwe in this year alone.

Nevertheless, “failed state” is a loaded term. The fact that seven out of the ten worst performing countries are located in sub-Saharan Africa paints a bleak picture of a continent already heavily burdened with negative stereotypes. Organisations like Fund for Peace, “are totally out of touch with the realities here,” says Ecweru. This may be hyperbolic, but the point is clear. No matter their intentions, insinuating from an Ivory Tower that countries are “failed states,” and understating or failing to give due credit to countries who have impressive gains in development is unfair, misleading and dangerously discouraging.