Exactly one month after Joseph Kony failed on the signing of the final peace agreement between the Lord’s Resistance Army and the government of Uganda, he again failed to meet a delegation of mediators and leaders from northern Uganda who traveled to meet him at the Sudan-Congo border on May 10. At Kony’s request, the team was meant to explain to him how traditional justice and the special division of the High Court would function following the signing of the agreement. His supposed confusion regarding these specifics was his most recent excuse for reneging on his April 10 commitment. Anyone surprised by the delay of this most recent meeting is hopelessly naïve about the motivations driving this process or has simply not been paying attention.

In our last interview with current LRA chief negotiator, Dr. James Obita, he told The Independent that “May is the D-Day” for Kony to sign the final agreement. But as Kony continues to dawdle and delay, no one has proven willing or able to hold him accountable to his increasingly meaningless commitments. When asked about the limits of patience for dealing with Kony diplomatically, UPDF/Defence spokesman Maj. Paddy Ankunda replied, “I hope you’re not asking me for a deadline.” This is precisely the problem. There is no deadline for Kony even though it may be the critical point in time to enforce one.

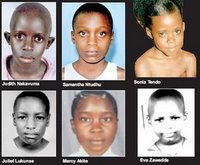

Principally responsible for what was once termed “the biggest forgotten, neglected humanitarian emergency in the world,” the LRA, with its band of elusive and internationally wanted war criminals, has today devolved into a festering regional force at once coming apart at the seams while simultaneously maintaining its infamous capacity to wreak havoc on innocent civilians.

With his failure to sign the final peace agreement, Kony unsurprisingly succeeded in further drawing out the “peace process” that has done everything but ensure that everyone involved take decisive steps to bringing peace and reconstruction to the region. Yes, the war as it was known in northern Uganda for over two decades appears to have ended but in the process, a new force has been spawned.

While the LRA of old was an isolated and relatively unknown force allowed to terrorise northern Uganda – through either the lack of capacity or lack of concern of the government of Uganda – the new LRA finds itself very much in the spotlight and unable to maintain the almost mystic aura that once surrounded Kony and company. Penetration into the once isolated bubble that was the LRA force has demonstrated to both the rebels and outsiders alike that despite his spiritual claims, Kony is after all just another man. There are signs of cracks forming among LRA leadership though rumours of infighting and Kony’s slaying of underlings may sometimes be exaggerated or even complete fiction.

The death of Vincent Otti last year was one of the first such cracks. Then came the almost comically frequent change of guard of the LRA chief negotiator. Martin Ojul was whisked away and replaced by David Matsanga who fumbled and fell, paving way for the entrance of James Obita – all in a span of five months.

And the LRA itself has been playing musical chairs across the region trying to locate itself in the most secure and strategic jungle spot, while hoping the music that is this bumbling peace process won’t stop playing yet. It darts from Garamba to Ri-Kwangba to Southern Sudan to Central African Republic (CAR) and back again, leaving behind smatterings of LRA camps and attacking and abducting as they go.

And whereas abductees and lower ranking rebels once feared defection – out of punishment by either the group itself or by the communities to which they would return home – a number of events and factors have succeeded in making rebel reintegration into society a much more attractive option for would-be defectors. It is perhaps the de-mystification of the LRA, together with increasing impatience with the drawn-out peace process, which has put Kony on the defensive and led to a spate of abductions throughout the region in the past few months.

Leader of the Opposition, Prof. Ogenga Latigo, thinks the cracks in the LRA are because its myth of invincibility has been shattered and Kony is no longer perceived as “godlike.” His followers and comrades have seen him very much humanised, interacting with local leaders and government officials who treat him as just another man and not the mystic spiritual leader he was once perceived to be.

Maj. Ankunda agrees. “His followers thought he was untouchable, unreachable,” he explained, but in recent years and largely as a result of the peace process, they have seen that “he can come out, he can talk…he is human.”

Kony himself is very much aware of his mortality and vulnerability, or else he would not be so concerned for his personal security. This has been the major stumbling block throughout the peace process. With an arrest warrant hanging over his head, issued by the International Criminal Court (ICC), Kony cannot be certain that if he surrenders he will not be immediately picked up and taken to The Hague, where he will most certainly be found guilty of committing the crimes of which he is accused.

The perceived vulnerability of Kony and his rebels has implications for the behaviour of the group. More members could see defecting or surrendering as an attractive choice in the months to come, even if Kony himself does not surrender. If these defections do occur, it may mean a weakening in the cohesion of the group. Kony could react with an upswing in abductions to rebuild his strength.

A UN report recently stated that 300 to 500 abductions had occurred in the region over the past few months. How well these new abductees will be able to build military capacity for the group remains to be seen. Though certainly cause for alarm, a heterogeneous group comprised of members largely uncommitted to a cause and under the leadership of a man increasingly perceived as vulnerable and paranoid may mean a new LRA that is more unstable. This does not necessarily limit Kony’s capacity to wreak havoc, but certainly suggests a new version of the LRA, and one that is not necessarily new and improved.

The vulnerability and incentives for the defecting of lower rank LRA should be an opportunity for interested parties to deal with the rebel group once and for all. Instead, the floundering of key players has all but ensured that this opportunity will be missed. The relative peace in northern Uganda today should not be taken as evidence that the government has done everything in its power to end the LRA insurgency.

In fact, the migration of the LRA has presented a convenient opportunity to deflect responsibility for dealing with the rebel group. As Maj. Ankunda explains, “Kony is no longer our problem, he is a regional problem.” Point taken: Recent abductions have occurred practically everywhere except Uganda. Unfortunately this has created a fabulous recipe for collective action failure. Kony is now both everyone’s problem and no one’s problem.

Pressure is mounting for Kony to sign, but he may have some time left to stall. The NGO community remains characteristically and naively optimistic abut the whole process, and though MONUC has threatened to take military action against the LRA, no one seems ready to pull the trigger and sanction or support such an attack.

So as the music continues to play, the LRA continues to frolic around the region stepping on toes, but never hard enough to elicit any consequential reaction. In fact, in some cases open and profiteering arms may even welcome the would-be mercenary force. And those who lie in the wake of the cavorting LRA are also those with the least power to do anything to stop them. With no government as yet severely encumbered by LRA occupation (and with some distinctly aided), the manhunt that could wipe out a recently weakened rebel force has yet to seriously begin.

The good news is that while perhaps not under tremendous pressure to capture Kony, the government of Uganda should find it in their interest to begin development and reconstruction of the now LRA-free north. Many observers have suggested that the government of Uganda itself has been complicit in war crimes or at the very least allowed the war to continue as a way of suppressing northerners not supportive of the National Resistance Movement (NRM) regime. However, Professor Latigo suggests that with Museveni’s slipping support in what were formerly NRM strongholds (such as Baganda and parts of the west), continued isolation of the north, intentionally or not, is no longer tenable. Indeed, Museveni’s recent trip to West Nile and elsewhere in the region suggests his keen interest in gathering northern support. And increased international attention on the conflict in recent years, largely as a result of the peace process, all but ensures that the north will not remain the forgotten humanitarian crisis it once was.

Nevertheless, though the myth of the LRA has been shattered, the mystical Kony brought down to earth and signs point to the potential devolution of the LRA, there appears to be more dilly-dallying. The government of Uganda has played their hand particularly well – simultaneously relieving themselves of blame and responsibility for the whole affair. But few in the region seem especially interested in picking up the reigns.

If one were to do away with the LRA once and for all, now would be the appropriate time to do so. It remains to be seen whether involved parties will take advantage of this window of opportunity, or instead dither and dawdle pushing around responsibility until Kony becomes the regional warlord he still has the potential to become.