Happy belated 2013! I hope your year is off to a productive start. I rang in the new year with friends and family in Kampala, where I’ll be based for the next nine months or so, during which time I hope to become active again in this space. I’m currently conducting dissertation research on the history and politics of Muslim education of sub-Saharan Africa, among other collaborations with colleagues and friends here in Uganda. More on that to come.

In the meantime, and in my downtime, I have determined to make 2013 a year of reading. I think this is my one and only new year’s resolution; the gym has failed me time and again. For a long time I felt guilty spending time reading things that did not directly apply to my coursework or research, a terrible way to go through life (and grad school). You can find inspiration anywhere, and the joy of reading is something that is easy to forget when you have thousands of pages of required reading.

So, I’m posting below all the books I read this year for my own records and as encouragement (I’m very much a list person. Makes me more productive). I’m more than happy to hear your suggestions on books you love, whatever the topic. The Economist has a great list of best of 2012 books here.

Last update: December 30, 2013

Key:

* Don’t bother

** If you have some free time, I guess

*** Fun, interesting, and/or worthwhile

**** Outstanding or an important read

***** Read this book!!

Fiction:

The Historian, Elizabeth Kostova ***

The Round House, Louise Erdich ***

Island Beneath the Sea: A Novel, Isabel Allende ***

Sweet Tooth: A Novel, Ian Mcewan **

The Cutting Season: A Novel, Attica Locke ***

The Garden of Evening Mists, Tan Twan Eng ***

Ghana Must Go, Taiye Selasi ****

Americanah, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie *****

And the Mountains Echoed, Khaled Hosseini *****

The Cuckoo’s Calling, Robert Galbraith (a.k.a. J.K. Rowling, yes I bought it right after I found out) ***

Beautiful Ruins: A Novel, Jess Walter ***

The Orphan Master’s Son: A Novel, Adam Johnson ***

We Need New Names: A Novel, NoViolent Bulawayo ****

The Lowland, Jhumpa Lahiri ****

Hard Times, Charles Dickens ***

Non-Fiction:

There Was A Country: A Personal History of Biafra, Chinua Achebe ****

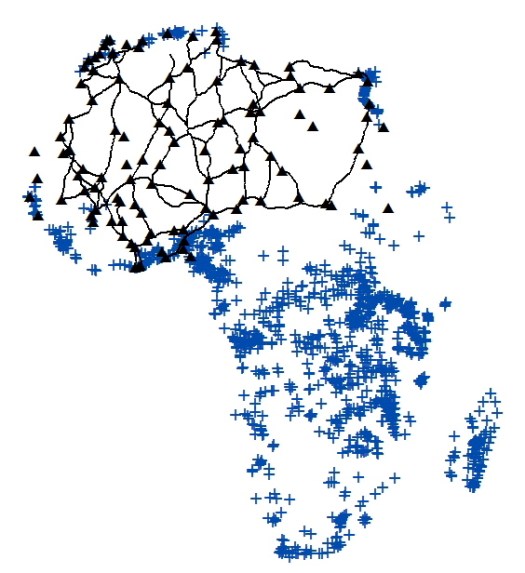

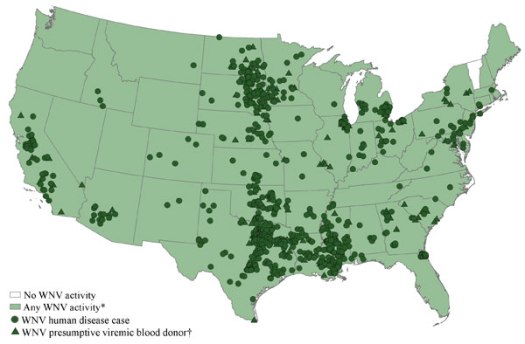

Spillover: Animal Infections and the Next Human Pandemic, David Quammen *****

Lean In: Women, Work and the Will to Lead, Sheryl Sandberg ****

Unorthodox: The Scandalous Rejection of My Hasidic Roots, Deborah Feldman ***

What I Wish I Knew When I Was 20: A Crash Course on Making Your Place in the World, Tina Seelig ****

The House at Sugar Beach: In Search of a Lost African Childhood, Helene Cooper ****

More Than Good Intentions: Improving the Ways the World’s Poor Borrow, Save, Farm, Learn, and Stay Healthy, Dean Karlan and Jacob Appel ***

Give and Take: A Revolutionary Approach to Success, Adam Grant ***

Predictably Irrational: The Hidden Forces that Shape Our Decisions, Dan Ariely ****

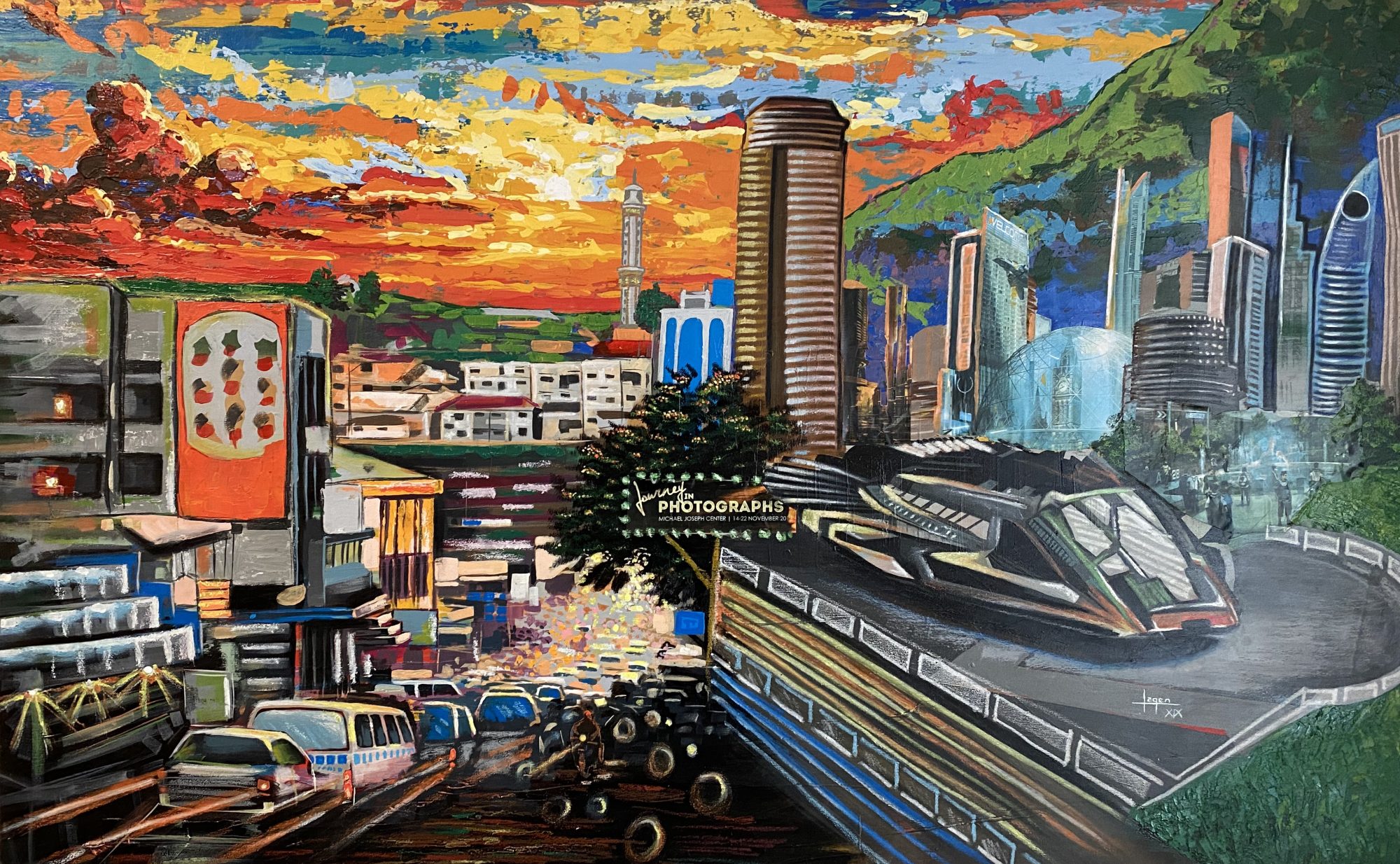

Triumph of the City, Edward Glaeser *****

Currently reading:

Sacred and Secular: Religion and Politics Worldwide, Pippa Norris and Ronald Inglehardt

One Day I Will Write About This Place: A Memoir, Binyavanga Wainaina

Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty, Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson

The Shadow of the Sun, Ryszard Kapuscinski