Published online March 19, 2012

After over 70 million views (100 million plus by the time this is published online) and countless tweets, the Kony 2012 video has reminded us of one thing: it is not quality alone that popularizes ideas.

Today, the marketing of your ideas matters as much or more than the content of the ideas themselves. At first blush, this seems a sorry or even scary state of affairs. But consider the evolution of the marketplace for ideas. Ideas have never found the light of day based on their merit alone. Access to bullhorns has long depended on identity – on status and class, on race and gender, on education and religion. Today technology is shaking things up, and democratizing the marketplace for ideas. The identity of the idea-producer is increasingly distanced from the idea itself. The barriers that once favored the voices of the few over those of the many are slowly fading.

Over the past week I have had countless conversations with students, friends, and even strangers about Uganda, the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA), Joseph Kony, and of course, the campaign and video that started these conversations in the first place, “Stop Kony 2012”. This sudden and remarkable outpouring of interest about a rebel group that has been around for decades is the result of the work of a single organization, Invisible Children. There have been spirited debates about the veracity of the film, ethical questions about its content, financial issues, concerns over the stated goals of the organization and film, and a larger debate about the role and motivation of outsiders in “African affairs”. Perhaps the most maddening aspect of the Kony 2012 film is that agency is so consistently placed on the part of the three filmmakers who “discovered” the conflict in 2003. (You have heard this story before. John Hanning Speke too “discovered” the source of the Nile – this is what has been “marketed” to pupils in most schools up to today). The version of the story told by Invisible Children tends to position the three men and their organization front and center at the expense of all other actors. It does not deal in nuance, and it shies away from complexity.

Critics of the film have struggled to put forth alternative versions of the evolution of the conflict, and the current challenges that the region faces, of which the LRA is only one. But many fear the damage has been done. They fear that Invisible Children has hijacked the conversation, pushing aside or simply ignoring the work that journalists, academics, policymakers, development workers, and ordinary citizens have been conducting for years. IC has proposed their own solutions to ending the terror of the LRA, which include sharing their video, buying an “action kit” (posters and bracelets inclusive), and raising money for the organization. They have virtually blanketed the web, at least for a period of time, with their own propaganda, their own ideas.

The phenomenal success of their campaign, at least as judged by the number of viewers, hinges not on the quality of their ideas and not on the feasibility or sensibility of their proposed solutions, as many experts will attest, but rather on their access to the platforms that get out the word. They are well equipped to execute their campaign – trained in film production, with a snazzy website and killer social media strategy, they have the all tools to dominate the marketplace for ideas.

Is this not unfair? Wrong? Even dangerous?

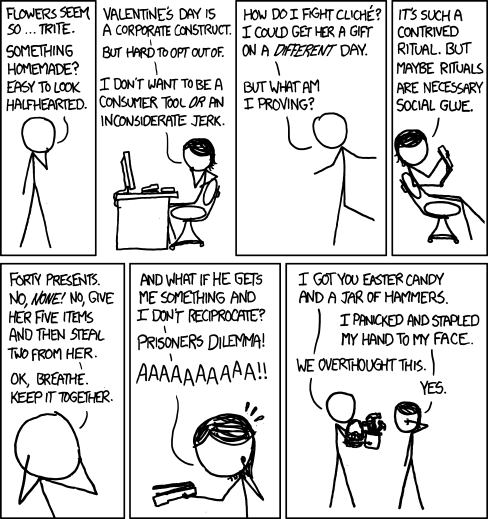

If the simplistic, emotive, and well-marketed ideas are the ones that make it to the global stage, should this not give us pause? Some argue that it is the very ideas that play to our underlying prejudices and the stereotypes that we find most moving (i.e. the west must “save” Africa), amplifying rather than dispelling our biases. They argue that the vast and diverse sources of news and information allow us to further distance ourselves from ideas we don’t like and fixate instead on those that support to our prior beliefs.

To the extent that government policy is driven by the masses, whether they take to the streets or to their Twitter accounts, should we be concerned about the quality of ideas that eventually make it to the mainstream? What happens when these ideas are the products of sleek marketing rather than of cool-headed and careful deliberation? These are all important questions.

The process that brings ideas to the center stage of public debate is not fair and does not give everyone equal say. Nor has it ever. But the good news is that the very technologies that have allowed IC to kick-start the conversation on the LRA have also allowed competing voices to fight back and provide an alternative view. In fact, in a departure from days past, social media may differ from the platforms of old in that it cannot easily be controlled to produce dangerous hysteria. You cannot stifle dissenting opinion for long in this day and age of hashtags and viral videos.

Perhaps IC has not hijacked the conversation after all.

Youtube, Twitter, Facebook, blogs, and other online media have allowed critics to respond to the IC campaign in real time. No sooner had the IC video come out than online posts pointing out its many flaws began to pepper the blogosphere. Within hours, IC had posted a response on their website, and the debate raged on. Journalists and ordinary citizens used online platforms to share their responses and concerns, and millions of people watched and listened. This is remarkable. The platforms that allow the dissemination of ideas are increasingly open for business. The marketplace for ideas, however flawed, is expanding.

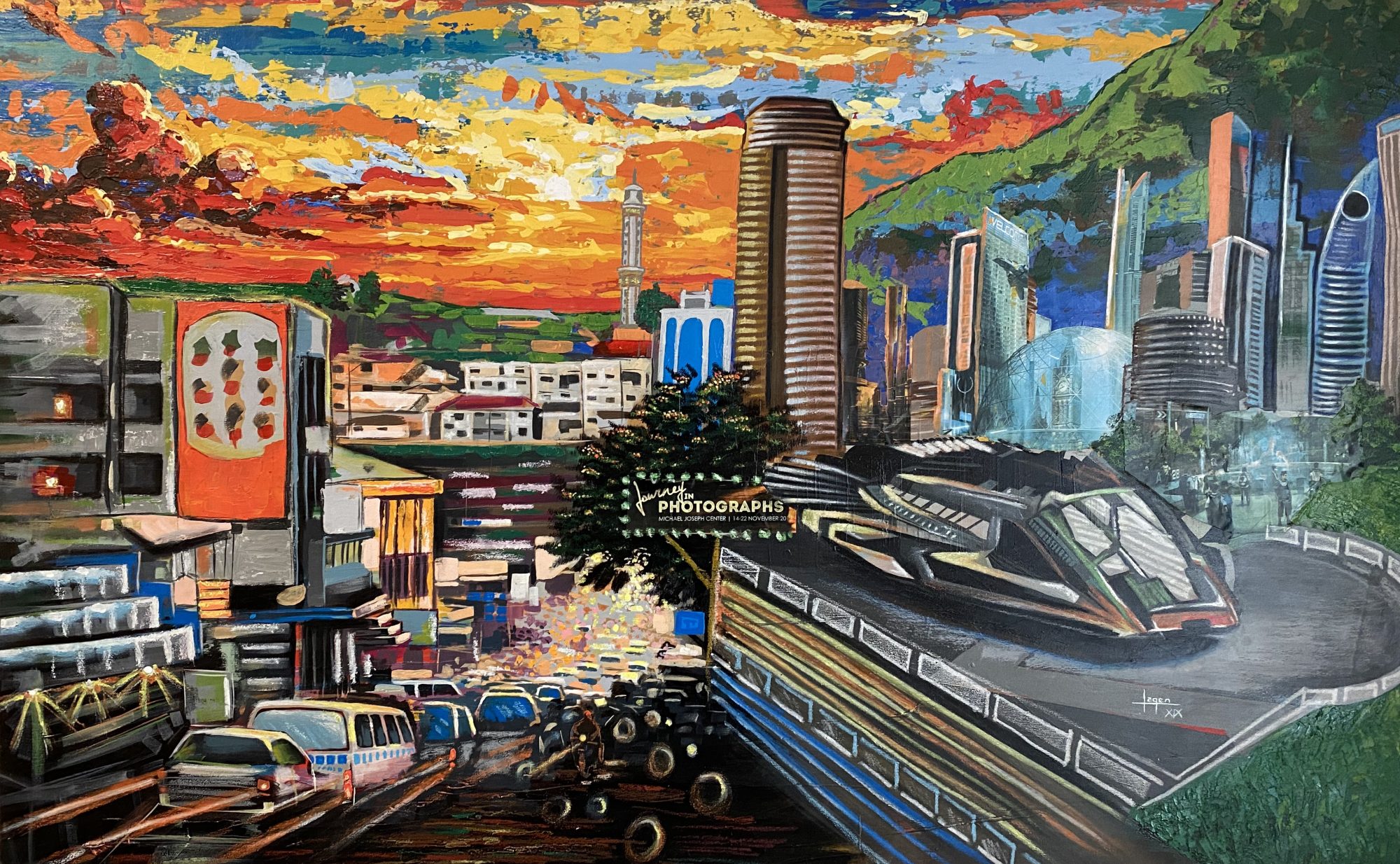

Don’t get me wrong. There is a long way to go. The fact that most people living in northern Uganda, even capital cities like Kampala, Kigali, and Kinshasa, were not even aware of the video (not that they missed much) only highlights the disparity in global connectivity, and as such, inequality in access to arenas where their voices can be projected loudly and widely. Those who set the agenda and those who have the first say in the debate are often still the most powerful not because of the quality of their ideas but because they know how to market them. The increase in information of all kinds means that people can seek out that which will confirm their biases and prejudices. But access to the microphone stretches farther than it ever has before. And this is good news. The question is what will we do with it?